Richmond street west in Toronto’s downtown is a one way thoroughfare with lots of traffic, day or night. Once you cross the light from University avenue and head west, there is a good three blocks before you hit a traffic light, so people tend to punch it. Drivers hit the gas, cyclists push hard. The walls of concrete and glass on either side of the street turn into a meaningless blur as commuters race to their respective destinations.

This is a city that moves fast. It’s speed is a reflection of the economy. A reflection of the many thousands that come every year, looking for a better life. Eager to start fresh. Make something of themselves. That speed is also a reflection of the real estate market. With a skyline now dotted with construction cranes, there are new glass towers popping off everywhere almost every day, it seems.

Richmond street is no exception. A number of buildings are being erected in the area, making way for residential condominiums and commercial businesses. Many of the clubs that opened in the 90s and 00s have been decimated. The brief era of hedonism in the entertainment district, it would seem, has drawn to a close.

The area is now populated with young, smartly dressed urban professionals glued to smartphones, less interested in dancing inside large scale clubs. More eager to make their mark at their respective careers, and content to stay in and watch Netflix at night. This is a new beginning for Richmond street, another era ahead.

Ma & Pa Assoon

Ma & Pa Assoon

Several decades earlier, and in a much warmer climate, a young Merchant Marine on shore leave from nearby Port of Spain, meets and woos a beautiful Trini girl. Sparks fly. Romance ensues, children follow. They are living in San Juan, a short trip away from the port. A city known for Solo Beverages; the popular fizzy drink maker in a country known as the Land of the Hummingbirds. The year is 1962. The socio-political background is tumultuous, at best. This is the same year Trinidad and Tobago is to gain independence from the British colonies. Although spirits are high, there is a feeling of uncertainty ahead. The mariner and his new bride head to the bright lights of New York for new beginnings. A fresh start.

The Assoon clan in Trinidad

The Assoon clan in Trinidad

The family is large. Seven children; five boys, two girls. One of the boys, named Peter, and the only one born in Brooklyn, tragically died three days after birth. They move into 402 Sterling Place, in the Prospect Heights section of Brooklyn. It is a beautiful brownstone home, and they make the most of it, with a party, or fete, every month. Calypso music is played, traditional Trini food like curried fish and pig’s tail is served. There is plenty of dancing, and laughter. The Assoon children are always present, taking it all in, absorbing everything.

In 1969, another event occurred on the horizon, outside the control of the Assoon family. Overseas, the Vietnam war was raging, and the looming draft troubled Pa Assoon. The prospect of losing either Albert or David, who were of potential age to don rifles, proved too much.

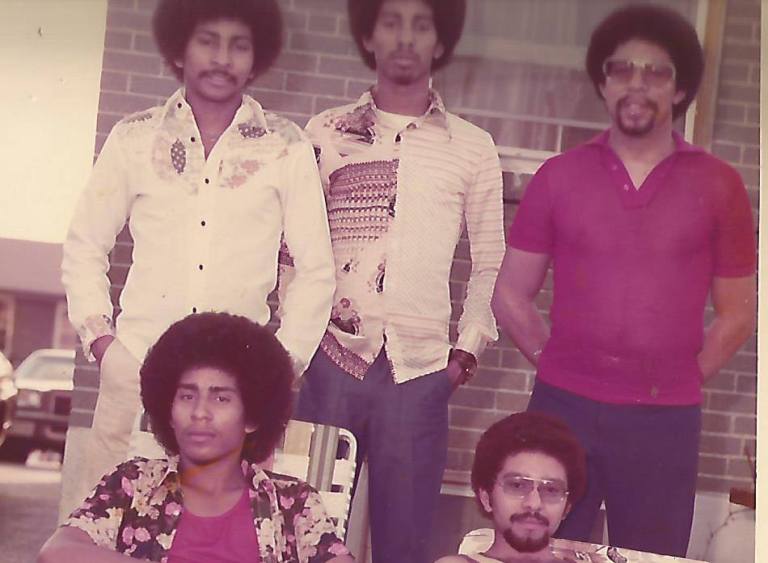

The Assoon Brothers. Top, from left: Earl, Tony and Albert. Michael & David below.

The Assoon Brothers. Top, from left: Earl, Tony and Albert. Michael & David below.

And so, the Assoons found themselves on the cold, grey streets of Toronto. Instead of holding rifles and grenades, they had luxury shoes and designer dress shirts in their hands while working retail jobs in the city’s downtown Yonge and Bloor area. But they just couldn’t shake a trademark genetic habit. Not unlike nectar to hummingbirds, the Assoons possessed a natural instinct of attracting people. They began throwing parties on a regular basis, just like their parents did when they were growing up.

The first event they threw as teenagers happened at their high school; L’Amoreaux Collegiate Institute in Scarborough. According to Tony, “It was the first Soul dance party which was a twist from rock and roll parties and people were like; they going to play soul music, ha ha. But it was packed and did well. It broke the ice for other schools to do the same thing.” The parties continued at their house in Scarborough at 301 Washburn Way. Then it spread back to the city’s downtown area. In basement recreation rooms below apartment buildings at 30 Isabella and 181 Sherbourne Street.

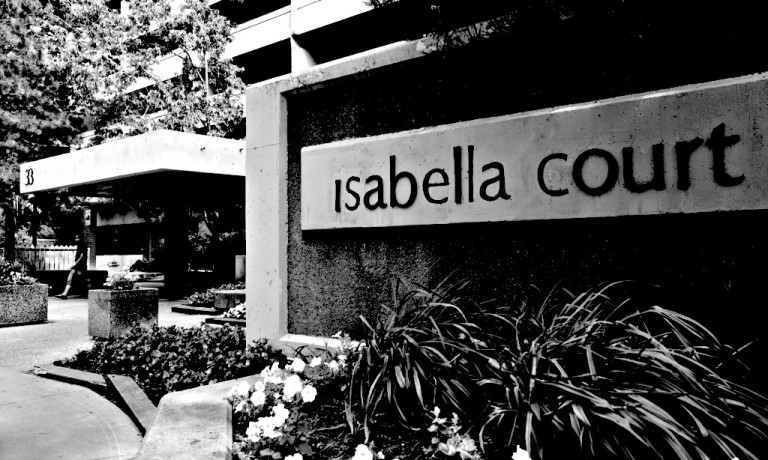

33 Isabella St. Toronto: A venue for the early basement parties by the Assoons.

33 Isabella St. Toronto: A venue for the early basement parties by the Assoons.

These parties were getting popular. But they were also getting expensive, and cumbersome. They first had to find a space, prep for the event, rent sound and lighting equipment for each party. When the party ended, which was always around the sun up hour for the Assoons, they had to clean the place up and return said equipment. This process was tiring, to say the least.

The first large scale effort from the Assoons was at a disco at Yonge and Bloor called Heaven’s. It featured New York singer Sharon Redd. They brought Kenny Carpenter to DJ the event. The brothers had dreamed of hosting such a night ever since their high school days, in their family living room watching Soul Train on television. The event did not earn them much money, and some of the performers were kicking the lampshades in the hotel later that night, in frustration. Despite this setback, the Assoons were far from discouraged.

The year is 1979. And the Assoons are on the hunt. They are looking for a new space to call their own. Most of the clubs at this time are in the St. Joseph area and Yorkville. Disco is huge. Almost too big. Every restaurant had a disco floor, that would light up at night.

In certain corners of the world, there was fierce resistance against the popularity of disco. It was too black, too gay, too happy, for some. In Chicago, Illinois, the same city that would one day play host to the creation of house music, a shock jock dj held an event that blew up disco records before a baseball game. The event is widely regarded as an explosion of intolerance by the rock-loving, mostly young white males. Historically, it became known as Disco Demolition Night, and for many, marked a significant ending for the popularity of disco, which had reached, many felt, a saturation point.

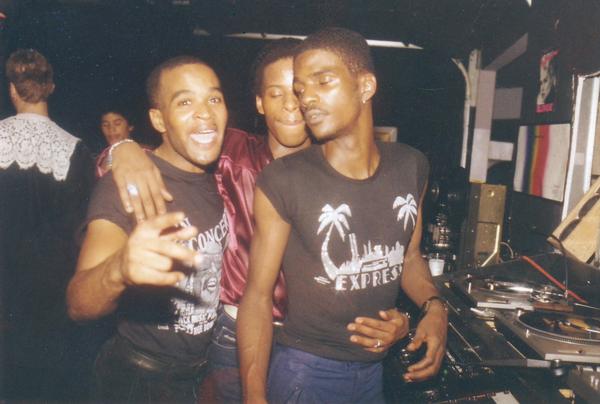

Kenny Carpenter (Far Right) at Bond’s Casino, NYC. Photo by Jose Infante

Kenny Carpenter (Far Right) at Bond’s Casino, NYC. Photo by Jose Infante

While those records were burning inside a baseball stadium, the Assoons are still spending time in New York. What at first glance seems like straight up partying for some, is actually serious research towards a doctorate in the art of the club experience for the pair. They are studying at the Paradise Garage. Melon’s in the East Village. Studio 54. Bond’s Casino in Time’s Square. Michael recalls seeing a show by Luther Vandross at 3AM with Tony that had a profound effect for both of them. I have a friend, James Applegath who coined the phrase the Golden Era of Raving in Toronto occurred in the short time frame between 1993-95. If that’s true, then the places the Assoons were frequenting in the late 70s and early 80s, represented the Golden Era of clubbing in New York City.

Flyer for Melon’s in NYC. Courtesy of Steven Mewa

Flyer for Melon’s in NYC. Courtesy of Steven Mewa

Michael and Tony aren’t just wallflowers at these seminal spots. They are interacting. Meeting people. Forging relationships that will alter the trajectory of the Twilight Zone, and in fact, the entire city of Toronto. Kenny Carpenter has a residency at Bond’s. They also meet Mike S, a promoter for some of New York’s hottest clubs that featured people like Frankie Knuckles, Tee Scott and Larry Levan. They meet Mike Stone, a promoter that represented Studio 54 where Kenny also played records. Comiskey park was worlds apart. This was an underground scene a million miles away from commercial top 40. For many of the gay, black and Latino clientele, this was a scene that was not only exploding; it was truly liberating. Freeing.

Taking a page from the Garage, the Assoons shunned the traditional route of available glitzy club spaces, and turned instead to the garment district. An area filled with warehouses stuffed with old ladies hammering away on sewing machines during the day, sitting empty at night. They first came upon a location that featured a theatre company. They would take it over at night for events. The location had the ominous address of 666 King Street West.

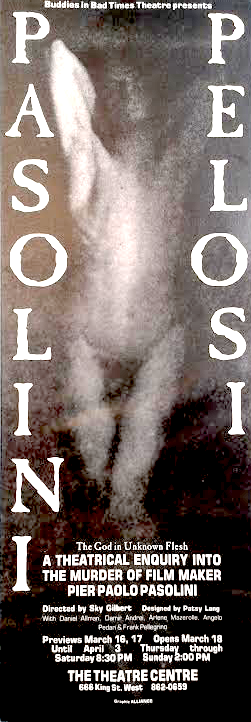

Poster for The Theatre Center, 666 King St. West. Courtesy City of Toronto Archives.

Poster for The Theatre Center, 666 King St. West. Courtesy City of Toronto Archives.

It worked out at first. Until they ran into issues with a powdered substance. Not the kind consumed inside bathrooms through nostrils. Something far more sinister. There was a dust problem. And whenever the Assoons, who have by now, an extreme propensity for volume, held an event, with each thumping bass line from the speakers, dust from the old wooden floorboards above would sprinkle over people’s hair, coat people’s drinks, get everywhere. They soon realized, this was not the space for them. The Assoon brothers returned to the hunt.

The Assoon Brothers with friend Michael Griffiths, far left. Photo by Charmaine Gooden.

The Assoon Brothers with friend Michael Griffiths, far left. Photo by Charmaine Gooden.

They came upon 185 Richmond Street West one fateful day, and history was born. The Twilight Zone was the only club in that area. During it’s hours of operation, you could feel the vibration from the club 2 blocks away on University Avenue. That bass you felt was courtesy of one Richard Long. The same guy that installed Studio 54’s and the Paradise Garage systems. They partnered up with Luis Collaco and Bromely Vassell, who remained tied to the business until 1983. The Assoon brothers got a loan from the bank to finance their audiophile dreams. Their father put the family home up as collateral, while his sons signed a waiver promising their unborn children would pay the debt if defaulted. Thankfully, It was a gamble that paid off.

Richard Long (left) with Roger Goodman, Installing the Twilight Zone sound system.

Richard Long (left) with Roger Goodman, Installing the Twilight Zone sound system.

They befriend two employees of world renowned sound system engineer, Richard Long. Ronald Holmes and Michael Joyner had a loft in Long Island city where they helped build speakers and circuit boards. They convince them to come to Toronto as architects for the early days of the Zone.

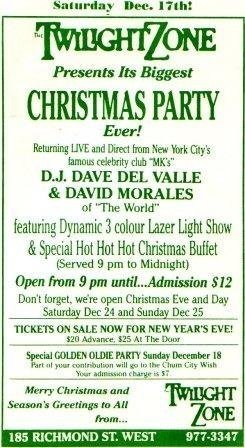

Once the system was in place, they began importing DJs they met while clubbing in New York. The job fell to Tony, who booked disc jockeys so eager to spin on a Richard Long system, according to Tony, “they were almost crying for it”. David Morales was one of the first. Johnny Dynell, a dj from NYC’s Save the Robots called Tony over to him one night. “I got this kid that’s really hot”, he said. “You got to hear him”. Morales’ longtime manager Judy Weinstein, agreed to the booking, with two exceptions. First, that they pay for her to come as well. Second, the fee was 500 dollars plus airfare and accommodation. At the time, the price was steep for the Asssons. But they agreed. Frankie Knuckles followed. Morales and Dave Del Valle played together. Kenny Carpenter came up. David Depino, another Garage DJ, also came up for a night with Morales, the same year For most of these DJ’s, including Knuckles and Morales, it was their first trip outside the United States. The Twilight Zone was one of few places in the world, to regularly feature guest djs.

The Assoons’ relationship with Judy Weinstein was not limited to booking disc jockeys, however. Weinstein also happened to run For The Record, a highly exclusive record pool, which the Assoons were able to access. This was the same pool that the world’s top dj’s were members of, including Frankie Knuckles and David Morales. For The Record was the reason that the Twilight Zone featured music that none else had access to. Some of the releases would not arrive to the public for up to two years. When starry eyed music lovers would walk into record stores in Toronto, they would ask the owners if they had any Twilight Zone music. This was well before the internet age, before Soundcloud, Youtube or Napster. You simply could not hear this music anywhere else, except in very select few scenes, like New York’s Paradise Garage, or Chicago’s The Warehouse.

For The Record was not the only source of vinyl for the Assoons. Tony also frequented Downtown Records and Vinyl Mania in New York city. It was a process that often times proved both euphoric but exhausting. Typically a day of shopping would involve a minimum of four hours of listening to track after track. Shop owner Manny Leaman would, according to Tony, “…work the records with the cross over while you made your mind up if you wanted the 12-inch or not. If it was really hot, you had to say yes in 30 seconds of hearing the track.”

Exterior, Twilight Zone. 185 Richmond St. West

Exterior, Twilight Zone. 185 Richmond St. West

Saturday nights featured a regular residency of Albert and Tony. Albert tended to play a steady mix of reggae, world beat, ska and disco, while Tony focused on the underground disco and funk he fell in love with in New York. They were also dropping Hip Hop bombs, well before you’d be able to find them on Toronto’s local radio station airwaves. During Caribana season, the Zone, in Albert’s words; “Jammed the best Calypso.” They were also spinning R&B gems too, like Gap Band, Dennis Edwards, and Alicia Myers. As soon as House music dropped in the mid 80s it quickly became an essential regular Saturday night ingredient. When the Assoon brothers would finish their sets, they occasionally let some young up and talent take over the decks, including Dave Campbell and Nick Holder, both teenagers at the time. Many other DJs, like Mitch Winthrop, were in regular attendance, and inspired by what they saw at the Zone, followed a pathway blazed by the Assoons.

Friday night flyer at the Zone. Courtesy of Norbert Ricafort.

Friday night flyer at the Zone. Courtesy of Norbert Ricafort.

Over time, they befriended Scottish DJ Don Cochrane, who would preside over their wildly popular Friday nights, that featured a UK dance party theme. Derek Perkins, who began spinning records downstairs at the Zone’s Night Gallery space, eventually also moved upstairs to take over on Fridays. The fusion of the seemingly opposite elements of the club created a crossover effect, with Friday night Goths, punks and skinheads coming to the House night on Saturday, and the often fashionable Saturday regulars showing up on Fridays. The spirit of the Zone created a deep love of all genres of music, and respect for one another. Many feel this was due to the chemistry of the Assoon vibe.

Wednesdays were dubbed Pariah, and featured DJs Siobhan O’Flynn and Stephen Scott. This night featured a blend of Psychedelia, Rock, New Wave, and everything in between. Although the night only ran for two years of the Zone’s history, people still speak fondly of it. Stephen recounted a fateful night where DJ Chris Shepard walked in and handed him a freshly pressed copy of a remix he did for Skinny Puppy track Dig It. They threw it on immediately and the crowd went insane.

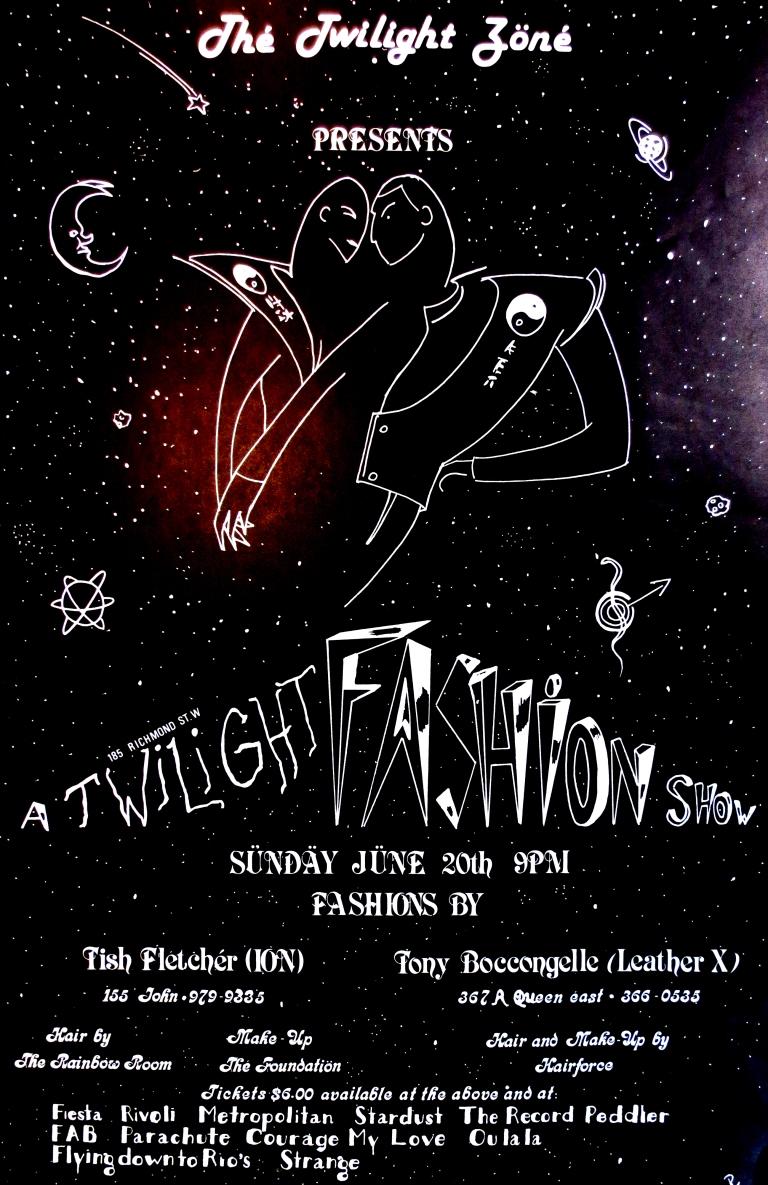

There were also many fashion shows, choreographed by Donald Carr. Fashion icons Dean and Dan, Peter Cox, Stephen Wong and Keith Richardson all called the Twilight Zone Ground Zero for Fashion forward peeps in the city.

Poster for Twilight Zone Fashion Show, Courtesy of City of Toronto Archives

Poster for Twilight Zone Fashion Show, Courtesy of City of Toronto Archives

From a music culture perspective, a lot of stuff was happening in the 80s. Hip Hop was still exploding, and the Assoons brought in a number of acts, including LL Cool J in 1984. They also brought in Sly Fox, and SOS Band. According to Albert, they booked Dynamic Breakers in 1984, after seeing them on television, either in a music video or in Style Wars. But if you look at the flyer below, the date references their second anniversary. This would put the date two years previous, in 1982. Whatever the case may be, they sold out the show, and had to add another night. Like Frankie Knuckles, David Morales, and so many others, performing at the Twilight Zone was the first international gig for the performers.

Jonathan Gross, a writer for Rolling Stone, and music critic for the Toronto Sun, also booked shows that featured some of these early Hip Hop acts. He convinced the Beastie Boys to play an after show party at the Zone after performing with Madonna during her Like a Virgin tour. They got caught spray painting the walls of the club with graffiti by Michael Assoon. Instead of telling them to stop, he urged them to resume. The Zone wore it like a badge of honour for the rest of it’s days. The day before the show, they showed up for a Pariah night, according to Stephen Scott, “wasted”. They got kicked out of the DJ booth by Siobhan O’Flynn. According to Gross, they got paid 1500 dollars and a case of Molson’s for the gig.

Alton Miller and Derrick May were Twilight Zone regulars, in the early 80s. According to Albert Assoon, Derrick May, a member of the Belleville Three, and widely regarded as a founding father of Techno, brought some vinyl and played one day in 1985. When Albert told me this during an interview, I nodded and made a note of it in my notebook. It wasn’t until months later while editing that this bombshell exploded in front of me. This was very likely the first time Techno music was heard in Toronto. And quite likely, in Canada. This was a full two years before May would go on to tour the UK for the first time, following the success of his Strings of Life hit.

There are countless other performances that took place at the Zone. Attending New York’s American Music Week, the Assoons were able to catch many memorable shows that inspired them to bring them up to Toronto, including Divine. Many of the American acts, according to Michael, were booked through the Norby Walters Agency through Cara Lewis. D Train, Fonda Rae, First Choice, and Adeva. After seeing Eartha Kitt perform at the Imperial Room, the Assoons booked her through legendary PR man Gino Empry, who has since passed. He had urged them to book her as she needed the business. Her one stipulation was that champagne would be provided, along with a long stem glass for her performance. The Assoons did not disappoint, and neither did she. There was also plenty of Canadian content present, like The Parachute Club and The Spoons; the list goes on, but some memories of the Zone are as cloudy as the smoke emanating from a dry ice machine.

The Zone also featured an all night buffet, a necessary stipulation of the archaic city municipal bylaws. After compiling a report, Toronto City Council would eventually designate the area the Entertainment District, deeming it the most sensible spot downtown for late night entertainment. The Assoons had planted a seed that germinated, and at once seemed unstoppable. A string of clubs ensued, spreading like wildfire, beginning with Charles Khabouth’s StillLife, two blocks West.

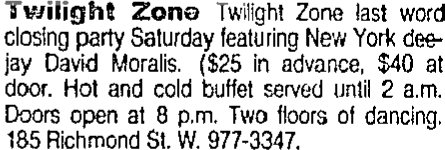

The Zone closed it’s doors in 1989, when the lease expired, and the landlord wanted a parking lot to replace the building.

Closing party Advertisement, Toronto Star.

The Assoons would continue to contribute to Toronto’s club scene for many more years with clubs like Fresh, Gotham, The Living Room, and their latest effort; Remix Lounge. But there would never be another Twilight Zone.

Back on Richmond Street, present day. The parking lot paved over the old bones of the Twilight Zone has given way to a yet another condominium in a city currently exploding with shiny new developments erasing it’s bricks and mortar past. A passing car kicks up dust and dirt from the construction zone. The car’s sound system booms that unmistakable four on the floor signature of a house groove.

Somewhere, somehow, the beat goes on.

A recent campaign has been launched to name a lane in honour of the Twilight Zone and it’s owners. Click Here to help out by signing the petition.

For more info on the Twilight Zone, check out my documentary Back To The Zone.

Featured, top image from Back To The Zone, original footage shot by Marla Rotenberg.

Leave a comment