Then the girl in the cafe taps me on the shoulder

I realize five years went by and I’m older

Memories smolder, winter’s colder

But that same piano loops over and over and over

– The Streets, Weak Become Heroes

I spent nearly two decades researching Toronto’s underground music scenes, some of which translated into a recent film near completion. Like many doomed projects, it started out with rather benign intentions. Having grown up under Irish Catholic immigrant parents, I was an odd duck in the Montreal suburb where I spent my early childhood until we moved to a Beaver Cleaver enclave North East of downtown Toronto; where I was also an odd duck there. Like a lot of other teenage weirdos, I found refuge and identity through music. As soon as I discovered music that was outside of the mainstream, I immediately took a shine to it, whether it was blues, jazz, ska, reggae, hip hop, dancehall, you name it. If I hadn’t heard it before, I was interested. Music offered unexplored worlds to me. I couldn’t resist traveling there.

I went to my first rave in 1993 which was two years after the scene first gained a proper sneaker hold in any type of meaningful way, at least in Toronto. From that first dry ice laced with green laser experience, I was immediately hooked on late night underground culture. Back then, there was plenty to explore, whether it was Pleasure Force’s The Rise on Fridays, a JMK warehouse party on Saturday, Gypsy Co-op on Tuesday, Mark Oliver’s Wednesday night at the Cameron, Thursdays at Limelight.

Even though I was just a kid, I knew there was something really special about that Technics SL-1200 soaked time period, something that needed recording. So eventually, once I got the courage (or more likely, the stupidity) to do so, I picked up a video camera and did just that. My purpose was to try and capture some of that riotous electricity present at such events. I’m not entirely sure why – I just felt those parties were important. And when you feel something is important, you want to document and share it.

I wasn’t only interested in the scenes that I was mainly steeped in – the wild frontier of raves or those impossibly cool warehouse parties. I was more fascinated with what connected those scenes to others – often seemingly completely separate subcultures.

What lessons have I gleaned over all these years?

First, there is a poverty connection. Punk was partly a reaction to the UK’s youth unemployment rate. Hip Hop originated in the South Bronx where there was also poverty and widespread disenfranchisement. House music was cathartic release for many gay black and latino community members in New York and Chicago. Poverty, disenfranchisement, these make for great ingredients for a desire to create something new. To release.

The early raves and warehouse parties were often housed in abandoned factories where our parents might have once worked before manufacturing jobs abandoned urban centres, and often entire countries altogether; thanks to an increasingly globalized world. Not unlike the Z-boys in Dogtown hijacking unused pools to skate in, underground organizers re-purposed similarly vacuous zones to practice their craft.

Second, each scene thrived on a new sound. This was music largely shunned by mainstream culture and in the pre-internet age, often difficult to discover. This meant it was usually only found in select record stores or if you were lucky; college or possibly pirate radio stations. In most cases, you had to physically source it out in order to find it.

Flyer for Exodus’ debut event, held at 23 Hop. August 31, 1991.

On the dance floor at 318 Richmond St. West, DJs gleefully lobbed weapons grade audio bombs, setting off unknown pleasures for many of us. The primordial ooze that would later explode into entirely new genres. Jungle. Hardcore. Trance. Progressive. Whenever crews carried heavy stacks of vinyl up those stairs, they were laying a cement foundation that would set the course for so many others to follow, as surely as the Egyptians that built the pyramids. 23 Hop was more than a dirty warehouse. For many of us, it was a temple.

These were tangible scenes only discovered through word of mouth or written invitations. The rave phenomenon took warehouse parties, club nights or block parties one step further, capitalizing on secrecy: you had to phone a number to get the location only 24 hours before the event was held.

All of these factors made attending any of those events that more special. Your mere presence at such a gathering meant you were in the know. You knew the secret handshake. You were part of something outside of the mainstream.

And by being part of something underground, something slightly nefarious, you were immediately drawn in, voluntarily conscripted and transformed into a card carrying member of something larger than yourself. Not unlike a certain annual commodified party in the Nevada desert; the same axiom held true: There were no spectators – only participants. There was no room for dilettantes or casuals in a resistance movement. Make no mistake, this was war.

Join any army and you are assigned a rank and unit. Underground subcultures are no different. You were either a musician, DJ, producer, promoter, designer, scenester, dancer, club kid or dealer. Everyone had a role to play. The DIY ethic honed by rock n’ roll bands and replicated by punk degenerates got xeroxed by the hip hop crews, the house heads and the rave syndicates as easily as recording from tape to tape.

Exterior, 23 Hop. Photo by Chris Gray

One of the questions I love asking people over the years on camera is the same one I often still ask myself. Will this ever happen again? Will there ever be another youth culture movement as bold, dangerous or vibrant as any of those I investigated?

During the course of an interview I once conducted with music journalist Daniel Richler he remarked, “Beware men with greying hair when they warn you about how music isn’t what it used to be. Having said that, music isn’t what it used to be!” Nearly two decades later, a prophecy has seemingly fulfilled itself. It is often tempting for me to lament about our current state of music culture and to compare it to halcyon days gone by.

Technology has meant that we can now access nearly every type of music ever created by our own species. How can that be a bad thing?

It isn’t.

But by making everything accessible means that it is less exciting to discover it. A fledgling real estate market with large unused spaces in city centres meant that there were plenty of dingy places to dance in. That is no longer the case in most urbanized locales. Besides which, who needs to go out, when you can find a date, play a video game or watch pornography on your phone?

Our increasingly technology-based world has brought us together in many ways, but we’ve also never been further apart. Having easy access to make and share video has helped shed light on the darkness of our human nature (beginning with the Rodney king incident and countless of other police shootings and abuses of power), but it’s also prevented us from shedding normalcy and experiencing true wild abandonment, a rite of passage for generations that has now reached near extinction thanks to the fear of immortalizing awkward, imperfect photo ops on our modern day status bezel: our social media accounts.

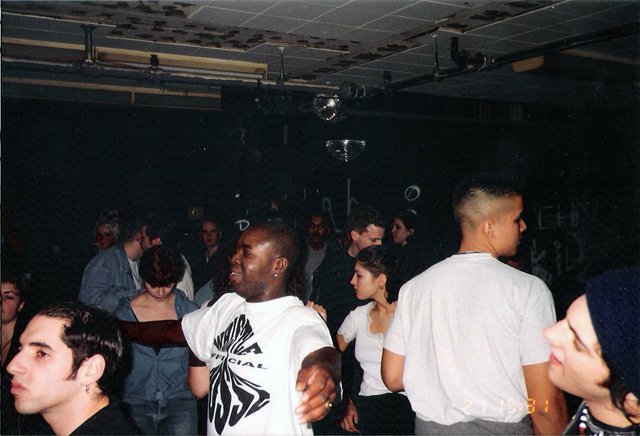

23 Hop Dance floor (front room). Photo by Chris Gray

But it would be a mistake to ball your hand into an angry fist and raise it to the sky while declaring; “Back in my day, things were different.” Because of course, it was different. Although there was certainly elemental poverty from a global recession in the 90s, there was also a palpable whiff of Downey fresh warmth from the blanket of positivity. The Berlin Wall had fallen. The Cold War had defrosted. The World Wide Web had just arrived. GPS would be introduced in 1995, but for many more years, before the ubiquity of smart phones; we would still use dance to find ourselves. Although we were among the first to embrace 808 tinged technology while the Seattle based grunge phenomenon seemed to frown in disapproval at us, our lives were not yet fully defined by it.

Things were looking pretty good. It almost felt like we were all finally coming together for the first time. That crazy MDMA infused party scene originating from the Balearic region and transplanted to the UK was not unlike the colourful Merry Prankster school bus that rolled into town. In both cases, nothing was ever quite the same.

When I initially embarked on this journey back through time, I was steadfast that it would not include any mention of drugs. Too many documentaries and biopics focus in on them, I surmised. But as I went deeper, I realized it would be disingenuous not to. I tried not to glorify or demonize it, but just like the hippies had LSD as their catalyst, the ecstasy pill serviced an integral portion of rave culture. It should be noted, that both are now being investigated by the psychiatric community as coping aids for depression, anxiety and PTSD. Although therapeutic levels might fall well below 23 Hop standards.

When Michael Stein, former owner of Pleasure Force Productions, comments on the rise of neo-liberalism in the film, he cites the success of raves as a reaction from an increasing disconnection from one another and the distribution of wealth being re-directed to the 1%. If he was right about things back then, we’ve landed right back to where we started.

But this anger and sadness that propels people to protest and fight is the same one that often sparks unbridled creativity. Conditions are therefore ripe for change.

Besides, young people will always need to dance.

I have to believe that.

I want to believe that.

Much has been said on Toronto’s real estate boom. And while it is important to celebrate all things bright and shiny, it came with a significant cultural cost. Dance floors have been decimated. New buildings built up. The kids that once danced together inside a smoky warehouse are now divided by cheap drywall and a mortgage. Hopefully, one day, someone will knock down those walls again and throw another party. The world sorely needs it.

Official Movie poster, The Legend of 23 Hop

Anyhow, here is part of that ongoing history. The year is 1989. After Toronto’s seminal Twilight Zone closed, a man named Ted Clarke has a party to honour a friend’s suicide which turns into regular ground shaking gatherings at his loft near Queen and River with DJs spinning Chicago house. Dubbed Kola and lasting only two brief years, the parties were legendary and would help solidify the template of the warehouse scene. Only a short while later, in the summer of 1991, after tasting the continental Acid House experience a bunch of Scottish kids from Brampton are audacious enough to start throwing regular whistle blasting parties at 23 Hop. Like Kola, Exodus gatherings would be short lived but retain mythical status. They would help signal entire new movements with analogue production companies holding weekly events at 318 Richmond St. West or a plethora of other warehouse spaces for years to come. In all three cases, the city would never be the same.

I was never able to interview Anthony Donnelly, although we tried to connect on several occasions. Shep never got back to me. Wes Thuro provided some fact checking but politely declined an on-camera interview. There are a bunch of other key players that have since disappeared or moved on for whatever reason. I did what I could.

Dedicated to the late Don Berns (Dr. Trance), Jason Steele (Deko) & Iain Gerrard.

Special thanks to Emeralda Hogan for the inspiration, Jim Applegath for the information and Gillian Carrabre for the motivation.

As Donnelly might have said, make some fucking noise.

Leave a comment